Art in Politics - Sunak and Truss

26 August 2022

What can we learn about our next prime minister from the candidates’ tastes in art?

Francesca Peacock

Francesca Peacock is an art, books, and culture writer.

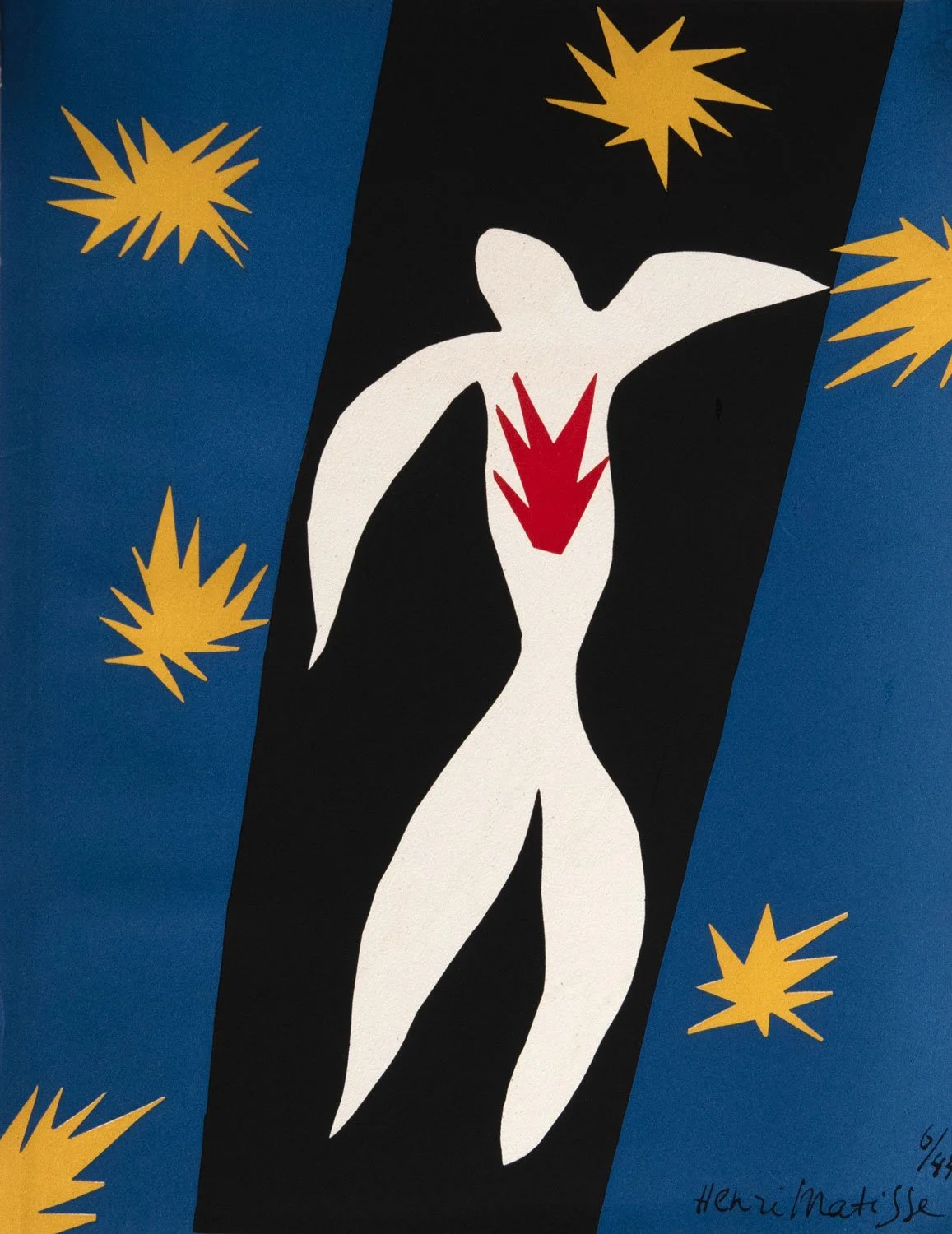

Rags to Polyester - My Story. Harland Miller (b. 1964). 2003. Oil on canvas.

Sold by Christite’s in 2012.

When it’s a late night of decision-making, campaign-running, budget-busting fun, what is the art that keeps Rishi Sunak company from his walls? What about Chris Burden’s famous 1977 work Full Financial Disclosure: a small, typeset pamphlet of the artist’s exact income and expenditure for the whole year. Looking at it now — with its detailed recording of his water and power bills, and his rent — takes on a whole new meaning with the looming cost of living crisis.

Or, if art about being skint isn’t quite Rishi’s thing — Burden’s net income for the year was $1054; he really should have re-trained in cyber — maybe Rishi would enjoy Andy Warhol’s “dollar” artwork. In the early 1960s, the artist had painted reams and reams of one dollar bills, but by the 1980s he had gone up in the world: rather than measly one dollar notes, he was painting colourful scores of dollar signs. Rishi would have to cough up though: back in 2009, Warhol’s 200 One Dollar Bills (1962) sold for the counter-intuitive $43.8 million, and a single dollar-sign painting can set the purchaser back $500,000.

But fortunately for Rishi, as for every other cabinet member, he does not have to pay for his own art: government MPs are allowed to choose works from the Government Art Collection to adorn their walls and offices. The Government collection houses over 14,000 works, and has a budget to keep acquiring new works — they recently commissioned prints by Tacita Dean, Lubaina Himid, and Hurvin Anderson. Sounds great right? It would be if the public could see it: the collection has no formal exhibition space, and works are normally only visible to the public if they happen to be visiting a Government building, or if works have been loaned to another gallery.

Such concerns seem not to have bothered the former-chancellor and would-be Prime Minister. As a result of an FOI request sent by The Spectator last year, it was revealed that Sunak had set up quite a collection from the Government vaults: Barbara Hepworth screenprints, Ivon Hitchens’s beautiful Two Poppies on a Blue Table (1957), and one of Graham Sutherland’s brilliant abstract works, Cornfield and Stone (1944). For a man who is so damning about the “value” of an arts and humanities education, Sunak certainly does reap its rewards.

And “value” is an interesting thing to discuss in relation to the Government Art Collection. One of the works that adorned Sunak’s Number 10 flat was Eric Ravilious’s Working Controls while Submurged (1941) — a colour lithograph of a submarine scene, made when the artist was working as a formally commissioned war artist. The Government Collection acquired it in 2002. They do not say how much for, but a similar lithograph (another one of the same edition of 50) sold for £1610 in 2000. For a Ravilious print, this is small change.

But many of the other works on Sunak’s works presumably cost far more: a Hitchens oil painting can reach £60,000, whilst a single screenprint by Barbara Hepworth can cost in the range of £7,500 - £10,000. Sunak chose eight of them. If he is cavalier about the prospect of defunding the arts, it would do Sunak good to remind himself how it is the government is able to afford these paintings — and how it is that the artists can afford to make them.

But for Sunak himself, these costs are pocket-change. It was recently discovered, by Colin Gleadell in The Daily Telegraph, that Sunak and his wife, Akshata Murthy, are collectors of one of Britain’s most highly-prized contemporary artists, Harland Miller. Their painting of his, Rags to Riches — My Story (2003) — appeared in an exhibition in 2020. It was bought at auction via Christie’s in 2012 for €25,000. The Sunaks have brilliant art collecting taste: Miller’s work now regularly goes for more than 10 times what they paid for it. Nor is this Rishi’s only foray into the world of contemporary art: this spring, he asked the Royal Mint to consider creating a digital NFT.

But if Rishi’s tastes at the Government Art Collection are anything to go by, he is more of a fan of mid-century abstraction and war-time art than he is contemporary work. If he wants to include more women in his collection, he should take a look at Marlow Moss. A radical lesbian, cross-dresser, and proponent of the industrial and USSR-originating school of art known as “Constructivism”: Moss might shock Rishi, but her geometric works would complement his Hepworth screenprints.

Foreign Policy, 2016. Tacita Dean. Chalk on blackboard

Image courtesy of Frith Street Gallery.

Only Room in my mind For you. Tracey Emin (b.1963). 2020. Acrylic on canvas.

Exhibited at White Cube in 2020-2021.

But what about the art-collecting habits of the other Prime Ministerial hopeful? Given her famed speech about the patriotic qualities of cheese, it would surely be a disgrace if Liz Truss were to favour anything other than British art. Luckily for her, the Government collection does have one work she might like: Brenda Noble’s lithograph Cheese Market.

But this wasn’t the work she chose. The Spectator’s FOI revealed that Truss picked Tacita Dean’s Foreign Policy (2016) — an artwork which the artist recently made into a specially commissioned print for the collection. It is hard to work out if this choice is part of Truss’s love of Dean’s dystopian photographs, films, and drawings, or if it was chosen for rather more practical reasons: Truss was Foreign Secretary at the time.

If we give Truss the benefit of the doubt, and assume she is, simply, a fan of contemporary women’s art, what else should she be collecting for the walls of Number 10? She is clearly interested in art which plays with the line between abstraction and realism (the clouds in the Dean work are meant to evoke an “epoch of unprecedented change and uncertainty”), so perhaps Tracey Emin’s most recent oil on canvas works might tempt the politician. The Government collection already holds some of her works on paper.

Or, if Truss is picking works on title alone, maybe she should pick Sonia Boyce’s Lay back, keep quiet and think of what made Britain so great (1986). With his recent comments about cracking down on “extremists” who “hate Britain”, this could be an ideal painting for Rishi, too — as long as neither politician looks at its intricately-woven message too closely. There is, perhaps, a limit to the power art can wield over politicians.

Francesca Peacock did try to contact both press offices about which artists Rishi and Liz preferred but was not unsurprisingly ignored – Francesca also submitted an FOI regarding what Rishi and Liz have chosen recently, but we are yet to hear to back.