Do Not Pass Go

24 NOVEMBER 2022

Jimmy Boyle: from life imprisonment to a life sentence as sculptor.

Jan Patience

Jan Patience is an author and journalist based in Glasgow. She has covered the visual arts scene in Scotland since 2007 and writes a regular art column for The Sunday Post.

Tom Allan

“Novel Waverly” 36x43cm marble, slate, travertine, and wood in a wooden box £800 available at scotlandart.com

Sculptor Tom Allan vividly remembers his first sight of Jimmy Boyle's work in Glasgow Third Eye Centre. It was February 1976 and the groundbreaking contemporary arts hub in the city's Sauchiehall Street, had been in existence less than a year.

For Allan, then a young English teacher in Glasgow, with a notion to pick up on his boyhood talent for art, seeing Jimmy Boyle's sculpture was a revelation. The irony was that Boyle, at that point almost a decade into a life sentence for murder, had created his art inside the city's infamous Barlinnie Prison.

"I recall it vividly," says Allan, now a respected sculptor, whose work veers between domestic in scale and the monumental. "Seeing Boyle's work helped to give me the notion to carve bits of demolished tenements in Glasgow. Just as he had done."

Soon, Allan was also carving chunks of reclaimed stone from tenements. He still carves in stone and marble, training with stonemasons in Scotland and marble-carvers in Carrara, Italy. Prices for Allan's work vary from £350 to £5,000.

In a career as an artist which has spanned more than 40 years, Allan went on to befriend sculptor Hugh Collins, another inmate of Barlinnie Prison's Special Unit, and the late Joyce Laing, the art therapist who introduced art to the hard men of Barlinnie.

There was a great deal of interest in Jimmy Boyle's sculptures from the moment the media picked up on the fact his Third Eye Centre exhibition was being staged while he was still in jail.

At the time of the show, as a prisoner, Boyle was not allowed to profit from his art. It wasn't until his release from jail in 1982 that buyers started to snap up his work.

The Special Unit, which opened in 1973 and closed in 1995, was the idea of senior prison officer Ken Murray and civil servant Alex Stephen. It was controversial from the outset, but the two men argued there had to be a better way of dealing with “uncontrollable” prisoners than locking them up in isolation.

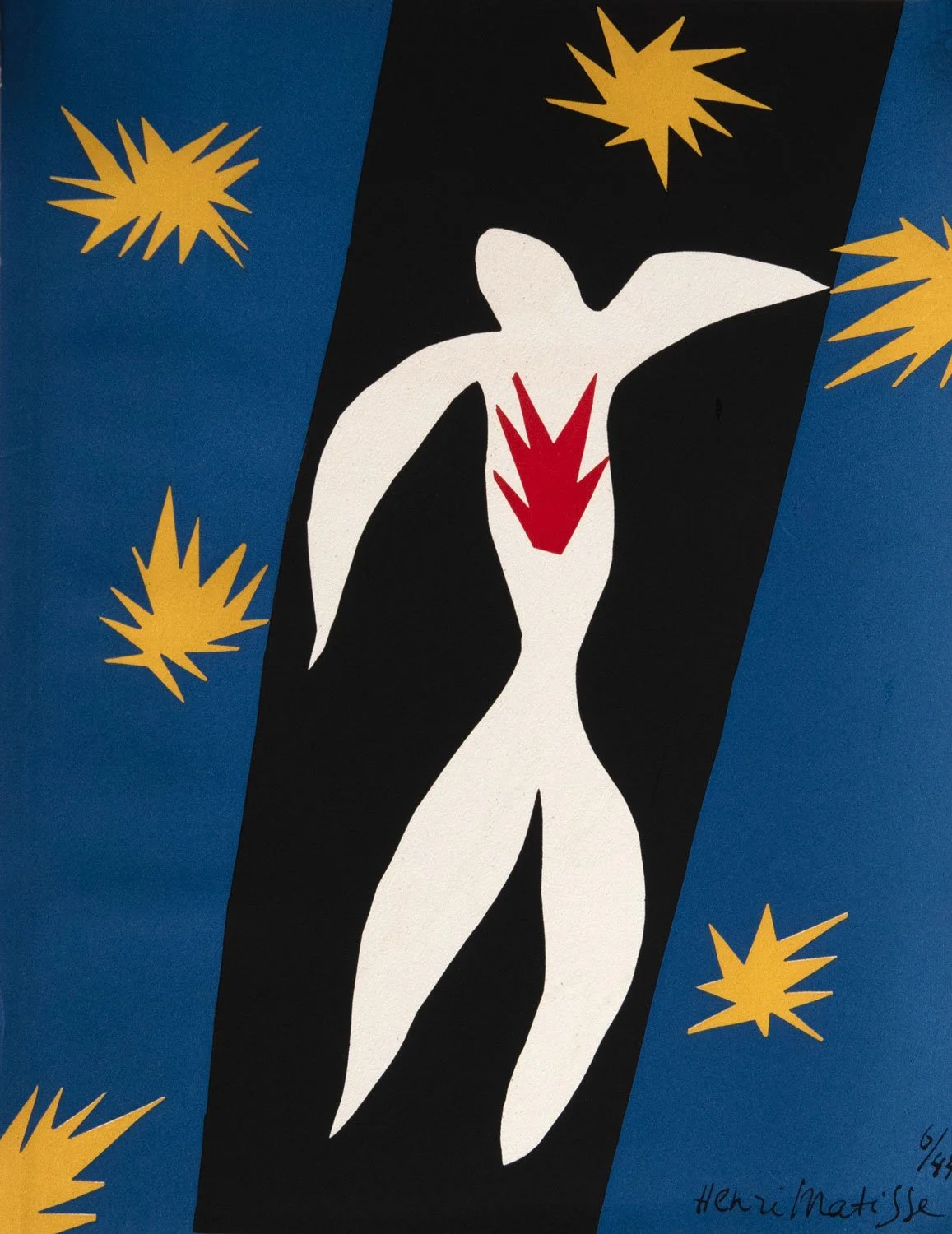

Joseph Beuys

Silver Broom and Broom without Bristles, 1972 available at Track 16 Gallery $180,000

It housed around ten men and with Laing's steadfast and doughty support, long-held barriers were broken down using art and creativity.

It was Laing who first offered Boyle a lump of clay. On her next visit to the Unit, she found Boyle had created a stick figure sitting down, surrounded by spear-like bars of a cage. From this raw beginning, the artworks started to pour out.

Boyle grew up in the notorious Gorbals area of Glasgow. He was one of the Unit's first inmates. At that stage, he was six years into a life sentence for the murder of gangland figure, William "Babs" Rooney. Boyle would serve 14 years before being freed in 1982. He was described in the newspapers of the day as "the most violent man in Scotland"; a man so dangerous he had served six years in solitary confinement.

Boyle wrote in the catalogue for his Third Eye Centre exhibition:

"…I had to experience creativity to realise how much I'd lacked it throughout my life. […] Am I an artist? If I am an artist then every single person on this earth is. I certainly wouldn't call myself an artist. What I would say is that I am a translator of my own 'feelings', from the intangible of my subconscious to the tangible of sculpture."

While in the Unit, as well as creating visceral sculptural works such as Solitary – Inverness and Thin Man: self-portrait, in 1977, he also wrote a best-selling autobiography, A Sense of Freedom, later turned into a film of the same name. He followed this with another memoir, The Pain of Confinement: Prison Diaries, and two novels.

A succession of high-profile artists beat a path to the Unit's door or offered support, particularly when in 1980, it was announced that Boyle would be leaving the Unit for a closed prison. Thanks to an intervention from Edinburgh gallery director, Richard Demarco, leading German conceptual artist Joseph Beuys threatened to go on hunger strike to draw attention to the decision.

In 1984, Boyle and his wife Sara Trevelyan, a psychotherapist whom he met when she visited him in prison after reading A Sense of Freedom, established the Gateway Exchange Trust in Scotland. The charity helps HIV patients, drug-related charities and disadvantaged children.

Jimmy Boyle

“Head of a Man” 37cm fibreglass

Jimmy Boyle, professional criminal turned sculptor, is the name most people who were around in the 1970s and 1980s remember from the Special Unit experiment. Although he didn't set out to be a professional artist, commercial interest in his work soared after he left prison. His work was bought for public collections and by private collectors.

But demand for Boyle's work has waned in the last ten years.

Following his release from jail in the early 1980s, Boyle's notoriety led to endless media coverage of his life and work. As the years progressed, however, he shied away from giving interviews to the press; particularly to Scottish newspapers.

As a result, Boyle's star – particularly in the art market – has fallen.

The last time a work by Boyle came up for auction, was in 2017 when a 37cm fibreglass sculpture called Head of a Man sold with Edinburgh-based fine art auctioneers for £650. In the years leading up to this sale, several works were put up for auction at salesrooms throughout Scotland with no resulting sales.

Today, 40 years after becoming a free man, Boyle, now in his late 70s, lives quietly in France with his second wife, actor, Kate Fenwick.

His role in a remarkable experiment which saw hardened criminals embrace their creativity is now the stuff of academic papers and TED talks, including one by Boyle's son, Kydd Boyle, about how changing the communities can shape behavioural patterns.

In a rare recent interview with BBC Radio Scotland following the death of Special Unit art therapist Joyce Laing, Boyle admitted that even today, half a century on from creating his first artwork, he still doesn't feel like an artist: "It was the first time I did anything positive in my life," he said. "It was a pure thing. It has stood the test of time"