Turns out Impressionism has a Dad

12 JanUARY 2023

Now that kids are back to school and crowds at Tate Modern are slowly dissolving, Francesca Peacock reminds us not to miss the major showcase of 19th century seminal painter Paul Cézanne (Tate Modern, London until 12 March 2023)

Francesca Peacock

Francesca Peacock is an art, books, and culture writer.

CEZANNE, Paul

The Basket of Apples, c. 1893 showing at Tate Modern until 12 March 2023

Bowls and bowls of brightly-coloured fruit — overflowing onto artfully ruffled tablecloths. Blue-toned groups of nudes, with their faces obscured with thick daubs of paint, standing around pools and lakes like figures from antiquity transposed to late 19th century France. Or endless, repeated views of the white limestone mountain in Provence, Monte Sainte-Victoire with patchwork fields in the foreground and increasingly Cubist, abstract ways of rendering the landscape.

If you’ve been to the Cézanne exhibition at Tate Modern — and managed to weave your way through the crowds to get close to some of the paintings — you will have seen some of these works: the famously colourful, enticing canvases of the French post-Impressionist, Paul Cézanne (1839 – 1906).

The exhibition is a comprehensive look at Cézanne’s life and career: from his “outsider” status in the Parisian art world of the mid-19th century (Cézanne was from Provence, and played up his “country boy” credentials), to his relationships with the “father of Impressionism” Camille Pissarro and the realist novelist Émile Zola, all the way through to the development of his signature colourful — but not necessarily jovial — style.

The exhibition has everything — from works which render Zola’s unflinching, realist literary style in paint, to haunting portraits of Cézanne’s son, Paul, all the way through to the jewel-toned fruits and “strange” compositions that he is now famous for.

CEZANNE, Paul

Les Baigneurs (petite planche), from Album d'Estampes de la Galerie Vollard. Sotheby’s

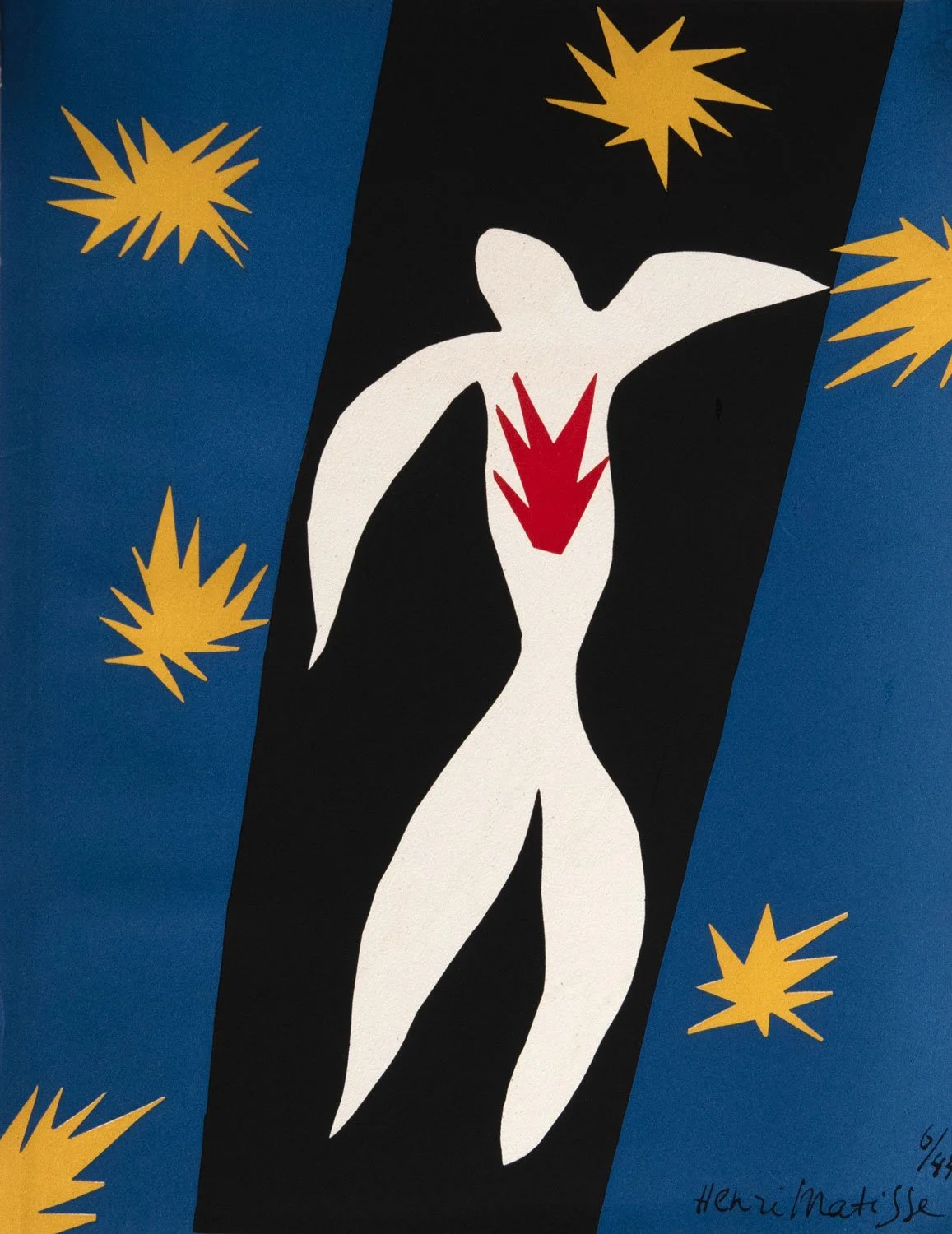

Alongside some of the paintings are tags indicating which artists owned the work: Cézanne was an “artist’s artist”, and everyone including Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse owned some of his pieces. His bathers, in particular, were an artist’s favourite: Matisse owned Cézanne’s ‘Three Bathers’, and turned to it for “moral strength” and “encouragement” throughout his life. In an interview in 1925 — 11 years before he would donate it to Paris’s Petit Palais — he declared that there are “constructional laws in the work of Cézanne which are useful to a young painter”. Henry Moore owned a different version of the painting, and even made a bronze figure of the three bathers — showing what “had been conceived by Cézanne in three dimensions”.

But how could these artists could afford Cézanne’s work — and paintings from his famous bathers sequence, no less? Few people could afford Cézanne’s latest auction record (set in November of last year) of $137.8 million — for La Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1888 – 1890), an example of Cézanne’s late style, but not one of his last studies of the mountain painted between 1904 and 1906. The hefty sum was a shock for the art world (the estimate was $120 million), but it was by no means unprecedented: back in 2001, the previous owner had bought the painting for the by-no-means cheap price of $38.5 million.

And back in 1999, Cézanne’s previous auction record had been set by Still Life with Curtain, Pitcher and Fruit Bowl (1893-94) which had sold for $60.5 million — making it the most expensive still life in the world. As if that weren’t enough, there are even estimates that the Qatari Royal Family paid between $250 million and $320 million for one of Cézanne’s 1890s The Card Players (at the time in 2012, it was reported to be the “highest price ever paid for a work of art“).

But if, as the Tate exhibition so wonderfully shows, Cézanne’s artistic life can be examined by considering his different styles, influences, and obsessions — then his commercial record is just as variable.

CEZANNE, Paul

Tete de Jeune Fille. Lithograph, 1873 est. $400-$600 at DuMouchelles

Back in December last year, Sotheby’s sold a lithograph of Cézanne’s bathers — an all-male group with prominent muscles which seems to be a sketch for the Bathers (1890-2) currently on display in the Tate — for a mere $7560. Whilst still not cheap, it’s a far more accessible way to own the inspiration and “moral encouragement” that both Moore and Matisse so loved. Just a few months earlier, in October 2022, a larger lithograph of a similar scene of male bathers sold for three times the price, at $25,200.

Oil paintings will, of course, set the purchaser back by rather more — but they need not quite require the whole wealth of an oil-rich nation behind you. Last spring, the rural scene La Fontaine sold for €730,800. On the other end of the scale, Christie’s recently sold L’Estaque aux toits rouges — a brilliant view of the sea off the south of France, with red rooves and trees in the foreground — for $55.3 million.

But there are other, more affordable ways to own a piece by the artist: his etchings — which so brilliantly show his way with light and dark, and his composition of the human form — are occasionally on sale for far less than millions of dollars. One auction next week (the 20th January) even has an estimate of $400 – 600 on an etching of a young woman, whilst another etching of a Provençal farm is going for only €180 at an auction house in Germany.

But it is, of course, true that nobody waxes lyrical about Cézanne’s prints — his etchings lack the colour of his still lives, and the undeniable strangeness of some of his compositions. For those, it seems, you either need to be filthy rich, or get yourself down to Tate Modern.