You Wouldn't Pirate a Book?

13 October 2022

Alexander Larman takes us sailing through the rocky seas of literary forgery.

Alexander Larman

Alexander Larman is the author of several historical and biographical titles including The Crown in Crisis & Byron’s Women. He is books editor of The Spectator world edition and writes regularly about literature and the arts for publications including The Observer, Prospect, The Chap and the Daily Telegraph.

Two typed letters signed to J. Gower Saunders. Regarding a Memoranda concerning the publication of the 'Life of Lord Randolph Churchill'. Together with a letter from Churchill's private secretary.

Available for £3000 at Peter Harrington Rare Books

It is a commonly known - and often lamented - fact that fake art has been big business for a considerable time. Indeed, some estimates suggest that as much as 20% of the art in British museums is either reproduction (putting it kindly) or fraudulent (to be more accurate). But in the gentlemanly, civilised world of book collecting, surely no such thing could happen, could it? After all, an expert could fake a painting with the right tools and equipment, but reproducing a book – especially one valuable enough to make the scam worth it – would be nigh on impossible, or so it would seem.

In fact, the continued popularity of antiquarian books has seen a rise in scams and frauds of all kinds, from the amateur opportunist forging an author’s signature and thereby hoping to transform an unexceptional title into a valuable one to the really dedicated ne’er-do-well, painstakingly piecing together various pages together to create a Frankenstein’s monster of a title. Although there has never yet been a fake copy of perhaps the most eagerly sought-after book of them all – Shakespeare’s First Folio – found coming onto the market, book dealers and collectors alike have found themselves bedevilled by reproduction dustjackets, carefully transposed title pages and even pirated editions of well-known titles, some of which, bizarrely, have themselves become collectors’ items in their own right.

For Chris Saunders, managing director of the legendary Sotheran’s bookshop in Piccadilly – soon to be featured in its bookseller Oliver Darkshire’s memoir Once Upon A Tome – it’s questionable as to why people bother. As Saunders says, ‘It takes a lot of time, money and expertise to fake a whole book and the rewards are unlikely to be worth it unless you manage to pull off a Shakespeare first folio. And even if you convincingly fake a 17th century book, there are easier and more profitable ways to con £2 million out of people.’

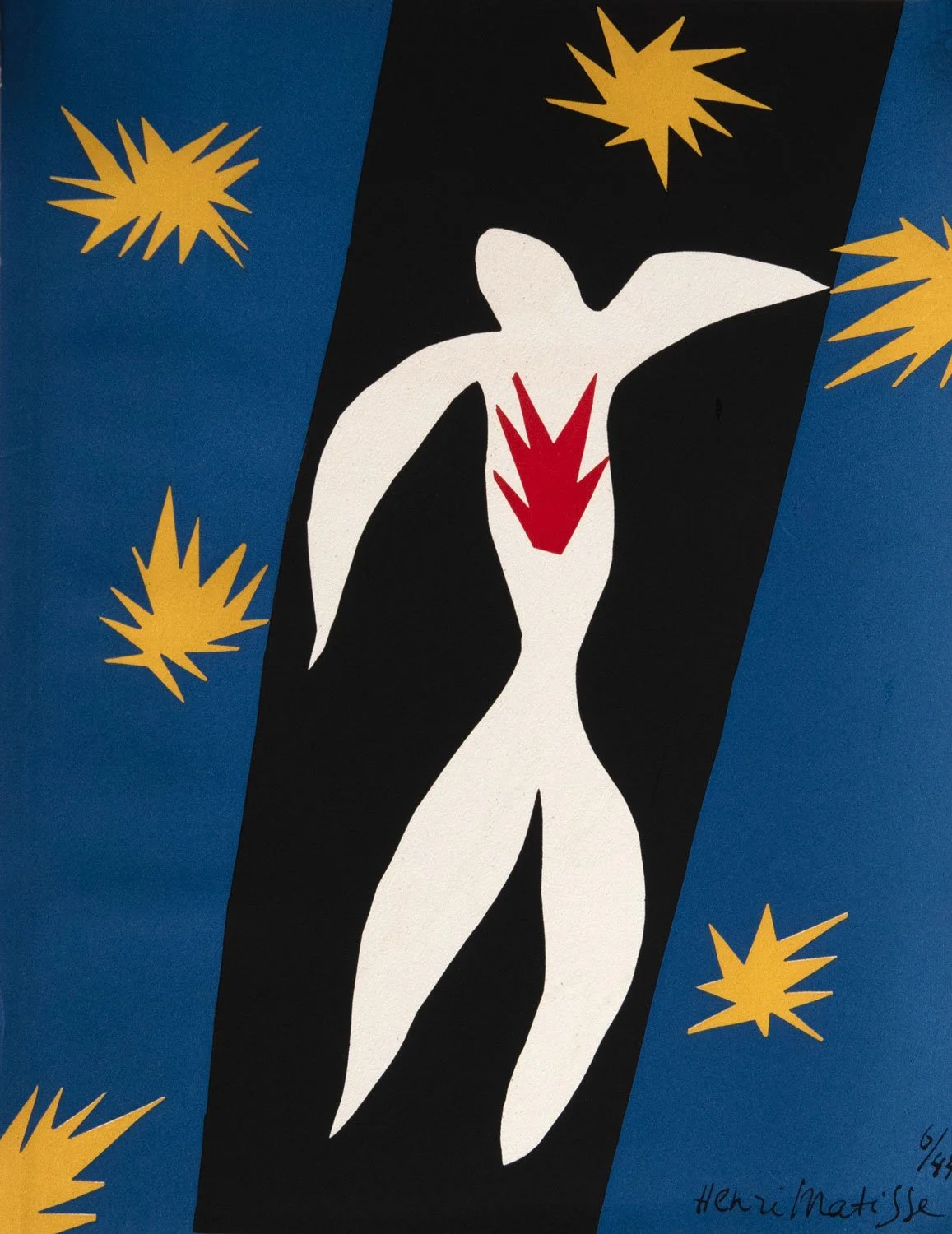

Juan Gris - “Le Pierrot au livre” 1924, Tate

This doesn’t mean that his shop isn’t subjected to the efforts of the unscrupulous. Saunders notes that ‘Fakery generally extends to signatures and dustwrappers – they’re much less labour intensive, and we have seen plenty of those. Dustwrappers are quite often faked, especially for modern first editions where a fine wrapper can add considerably to the value of the book. The James Bond novels are a case in point. We recently had someone try to pass off a whole collection of James Bonds with fake wrappers. Unfortunately for him, the wrappers all had ‘facsimile’ printed in very small type to the bottom of the front flap.’

As for signatures, they can be notoriously difficult to spot – or, if it’s a true amateur at work, laughably easy. But Saunders has come up against some true professionals in his time. As he says, ‘It can be very hard if a skilled faker has been at work. It takes a lot of skill, research and experience to authenticate a signature, and even then there can be differences of opinion. Some authors are easily and commonly faked, Winston Churchill for example. We have a general policy not to accept any Churchill signature unless it comes with an inscription or a letter, something that is less easily faked and that offers some background. Churchill was actually his own best faker - he often used an autograph inkstamp that looks like a real signature.’

Nonetheless, fake books can have their own value, especially if they were the pirated early editions of major titles. At the time of writing, John Lutschak books in the United States are selling the 1929 pirated edition of Ulysses – the ‘true’ first edition of the book – for £11,698, and the notorious ‘fake’ copy of Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray, which was was effectively stolen from Lippincott’s Magazine by a small American publisher within two days of publication, sold for £2680 the last time it was offered at auction. As Saunders says, ‘There are lots of examples of this kind of thing. Pirate editions are usually pretty low quality and therefore a lot of the copies have perished, so finding one can be a real pleasure, because they are rare and are important in the publishing history of important works - a book only gets pirated because its popular, or controversial, or both.’

The literature specialist Sammy Jay at London’s premier bookshop Peter Harrington, meanwhile, is a veteran of what he calls ‘sifting through a great deal of mud while panning for gold.’ He has come across a variety of low-level fakery in his career, which he summarises as ‘dust jackets sporting discreet and often undeclared restoration, genuine signatures from other books bound into genuine first editions in the attempt to pass them off as actually signed copies, or Charles Dickens’s bookplate removed from a boring book and put into a first edition of his own novels.’

A metamorphic set of library steps, mahogany. England circa 1860.

Available at Woodham-Smith LTD

Although he calls entirely faked books ‘very rare cases’, he has also seen a variety of historically interesting – if frustrating – antecedents. Jay says ‘You have to be particularly wary of signatures from the 19th century and earlier, especially for those writers whose signatures are rare and highly prized. Edgar Allan Poe is a classic example – his signature is rare, and very expensive when found. We were quite recently offered a book which had what seemed to be his ownership inscription in it – but on closer inspection it appeared to be a forgery, perhaps by the notorious forger Joseph Cosey, or Poe’s contemporary and rival Rufus W. Griswold who is known to have maliciously fabricated damning additions to Poe’s letters for his 1850 memoir of Poe. The owner was kind enough to donate the book to our “Black Museum” of forgeries, which remains with us as a helpful reference and teaching aid.’

Inevitably, both Saunders and Jay have come across the unscrupulous and the crooked, but, thankfully, book collecting remains a civilised and literate place, where the bad apples are vastly outnumbered by the genuine bibliophiles. And, as Jay says, there is an easy way for the would-be book purchaser to avoid being conned. ‘Take advice from a bookseller you can trust, maintain a healthy scepticism (without becoming closed-minded to the wonder of discovery), and try to get your eye in by actually looking at lots and lots and lots of books. Go to actual book fairs, visit actual book shops. In the long run, it’s experience, which in our world is fundamentally a tactile thing, that makes most of the difference.’ If it seems like a fake, then, it probably is – but you won’t be buying one if you’ve used your common sense first.