Sex, Drugs and Rock’n’Roll…for Nerds

17 November 2022

Alexander Larman talks to bookseller Carl Williams about our favourite things.

Alexander Larman

Alexander Larman is the author of several historical and biographical titles including The Crown in Crisis & Byron’s Women. He is books editor of The Spectator world edition and writes regularly about literature and the arts for publications including The Observer, Prospect, The Chap and the Daily Telegraph.

GINSBERG, Allen “This Style Hat was worn by self here signed. Vietnam War Protest March NYC 1966-7 Allen Ginsberg”.

Available at Carl Williams Rare Books £35,000

If you went into a respectable antiquarian bookshop and asked for their recommendations in modern literature, you are likely to be directed towards a series of brilliant and much-acclaimed writers, many of whom may have had complex personal lives but whose work remains top-drawer stuff. Yet if you were to ask ‘got anything slightly spicier’, you would either be politely shown the door – ‘we are not that kind of establishment’ – or you might, equally politely, be asked exactly where your inclinations lay.

In the case of the bookseller Carl Williams, perhaps Britain’s greatest authority on underground and counter-culture literature, there is no distinction to be made between, say, Virginia Woolf and Graham Greene and William S Burroughs and Alexander Trocchi – at least from a perspective of collectability. As he says, ‘Burroughs is very collectable, almost like a countercultural Ian Fleming in a way. He was picked up by the fashion, art and rock worlds which spread him far and wide. He gave good spoken word and so he lives on for cyber-eternity. I have handled lots of his material including his own Scientology workbooks.’

The Scottish novelist Trocchi, who died at the age of 59 after a lifetime of heroin addiction, is a different breed entirely. As Williams notes, ‘In volume terms, I’ve handled far more Trocchi. I sold the last parts of his personal and business archive to a college library in all of its burnt-and-covered-in-blood-spray-from-hypo-cleaning splendour. He was a truly great writer who, if you get the right book such as, for instance, the very rare publisher’s special binding of Cain’s Book, you would do quite well.’ (A standard first edition retails at around £300.)

DE QUINCEY, Thomas.

Confessions of an English Opium Eater First edition available at Peter Harrington £2,500

Yet the trouble with being a counter-cultural writer is that they do not keep regular hours, and are consequently vastly unreliable from a collector’s perspective. Williams tells me that ‘The problem with buying and selling Trocchi is that unlike Burroughs (who was a remittance man) he was constantly on the make for money to buy heroin. So he was in the habit of copying out his own books and selling them as the original manuscripts - which are fascinating in their own right perhaps.’ In this, Trocchi followed the original counter-cultural writer, Thomas de Quincey, whose 1821 book Confessions of an English Opium-Eater is perhaps the first drugs memoir in the English language. As Williams says of De Quincey, ‘he is part of the long established literary canon of great white dead white male authors and he was an incredibly insightful and prosaic chronicler of the opiate experience.’

De Quincey, like Burroughs and Trocchi, remains hugely collectable. Although Williams has never had a signed copy of Opium-Eater, he estimates that, if it had its original, fragile backstrip, it would be worth something in ‘the lower five figures’. One thing he has sold before is ‘a letter from De Quincey to his publisher moaning about the bad effects his several thousand laudanum drop a day habit had on him - and how he should take more to overcome the symptoms.’ Its sale remains a source of mild regret for Williams. ‘I think I charged in the low thousands for it and of course it turned up on the invite to the opening for the LSD Library, so I probably should have charged more.’

Williams began his own career in what he calls ‘an ancient, posh bookshop, where I was designated as ‘counterculture guy’. He began his career in the company of a collector – ‘we bought vast amounts of drugs, sex and rock ‘n’ roll together’ – and ascribes at least some of his success in his dealing to being associated with the writers who he has bought and sold. ‘I have met a fair few of the less famous counter-culturalists, and one or two better-known writers, artists, thinkers and inventors. They tend to be either great hustlers like the wonderful Felix Dennis of OZ infamy, or they are psychedelically much older than everyone else around them. For instance, take the great Sasha Shulgin, the stepfather of Ecstasy; I have some of the glassware that he used to synthesise the much more famous dance drug that he rejigged and sent out into the world.’

Williams believes that the reasons why counter-culture literature remains so collectable are clear. ‘There’s a bit of a twist in the tale as to why some of the psychotropic and countercultural printed books and their precursors are collected so ardently. It’s either that they become so very influential that the mainstream simply has to have them, or that they become tied to a significant event or person and they step out of the shade to bathe in the truly expensive sunshine of collectability.’

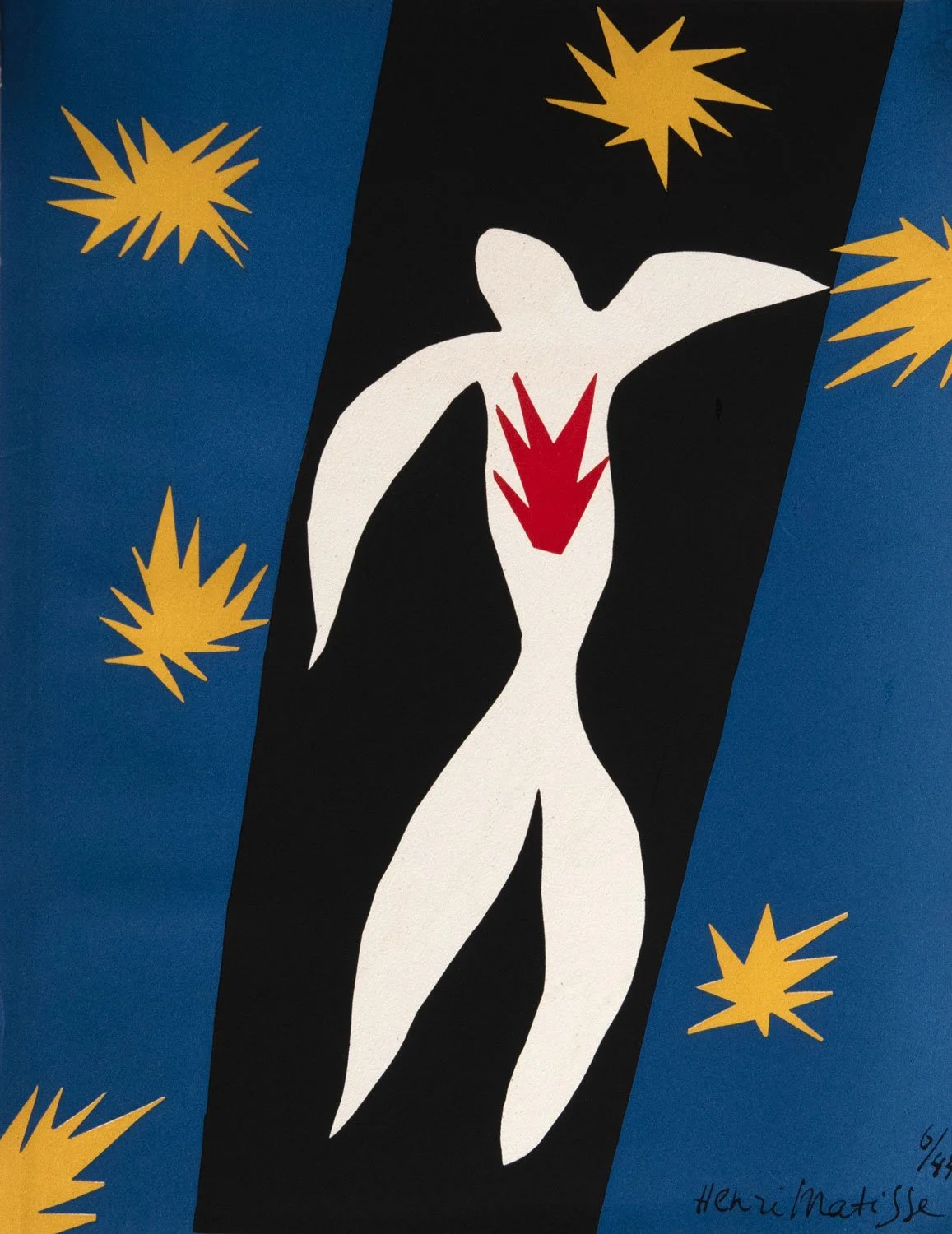

José Luis Cuevas

Autoretrato en un Fumadoro Chino, 1978, watercolor & Ink on Paper available at Stern Fine Art $5,500

Although he refuses to commit to suggesting which present-day writers are likely to be sought after in the future (‘I even have problems predicting the past’) he tips anything put out by the Fitzcarraldo Press and the work of the ‘Bourdieuan neo-Marxist’ Edouard Louis as potentially desirable. Yet as ‘white, dead males’ have become unfashionable to collect, Williams also suggests that work around race, sex and gender will usurp it; ‘Think Black Panther Party posters, the output of the Kali commune, the libretti for gay operettas in the café and bars of San Francisco and the posters of Paris Mai 1968. Think ‘thinkers’ like Buckminster Fuller. Think also of the clowns and prankster of the period such as The San Francisco Diggers.’

When it comes to the single most unusual item that’s been through his hands, Williams cites ‘the trip diary of the Mexican artist José Luis Cuevas, after he was injected in the neck with LSD’. In it, Cuevas wrote that ‘fantastic pictures of great plasticity arose before me…feelings of horror, indifference and contempt paraded before me.’ He describes the so-called ‘Holy Grail’ of counter-culture literature as the Marquis de Sade’s original manuscript of 120 Days of Sodom, which was acquired by the French state for over £4 million last year, but, when asked what he himself would most like to own, Williams has an apposite response. ‘Don’t get high on your own supply.’