Unreal City still Unrealised

8 DECEMBER 2022

The centuries-long struggle to capture the essence of London.

Joe Lloyd

Joe Lloyd is a journalist who writes about architecture and visual art for The Culture Trip, Elephant, and The Economist's 1843 magazine, among others.

Auerbach, FRANK Tower Blocks, Hampstead Road, 2007 available at Marlborough New York

London is a difficult city for an artist to capture. Rome has been ossified and Paris homogenised. Everyone knows what they look like. But London is a stranger beast. There are some consistencies — rows of terraces in stock brick, black-painted railings, ragged late Victorian and Edwardian high streets, tiled corner pubs, the red-and-blue roundel of the Underground. There are landmarks, such as the Palace of Westminster and St. Paul’s Cathedral, and an unavoidable natural feature in the form of the Thames.

But London’s palette and profile are ever shifting, from gleaming Portland stone to peeling stucco, stained concrete to shimmering glass. It makes the metropole both thrilling and hard to pin down into a single image, in the way a Haussmannian street corner can come to stand for the whole of Paris. Perhaps this is why London is best appreciated in literature, from Ben Jonson and Daniel Defoe to Patrick Hamilton and Iris Murdoch: it is a place that demands multiple impressions rather than a fixed image.

Nevertheless, some of the greatest names in the history of art have tried. Many of them have brushed with failure. Canaletto's imaginative renderings of Venice proved especially popular with the English. He moved to the country between 1746 and 1755, for a spell living in Soho, and set about attempting to do for London what he had done in his hometown. Though Canaletto created some fine vedute of the Thames, many found his work repetitive and mechanical when compared to his magical views of Venice. One critic even claimed that he was an imposter who had usurped the true painter’s name. This judgement has held true in the art market today: only four of Canaletto’s London paintings are included in his top 50 works sold at auction.

L.S LOWRY, Piccadilly Circus, London 1960 Christie’s

Over a century later, in 1870, a young Claude Monet arrived, fleeing conscription in the Franco-Prussian War. His paintings of Green Park and London’s docks have none of the freedom and luminosity that had already begun to appear in his French work. It may have been the weather, an attempt to appeal to English tastes or his own dark mood in self-exile. Or it may have been that smog-sheathed London itself failed to ignite his vision. Monet’s older contemporary, Camille Pissarro, fled the Prussians and ended up in suburban Upper Norwood. He brilliantly captured the then-rustic outskirts of the capital. But his work gives little insight into a metropolis by then double of the size of the French capital.

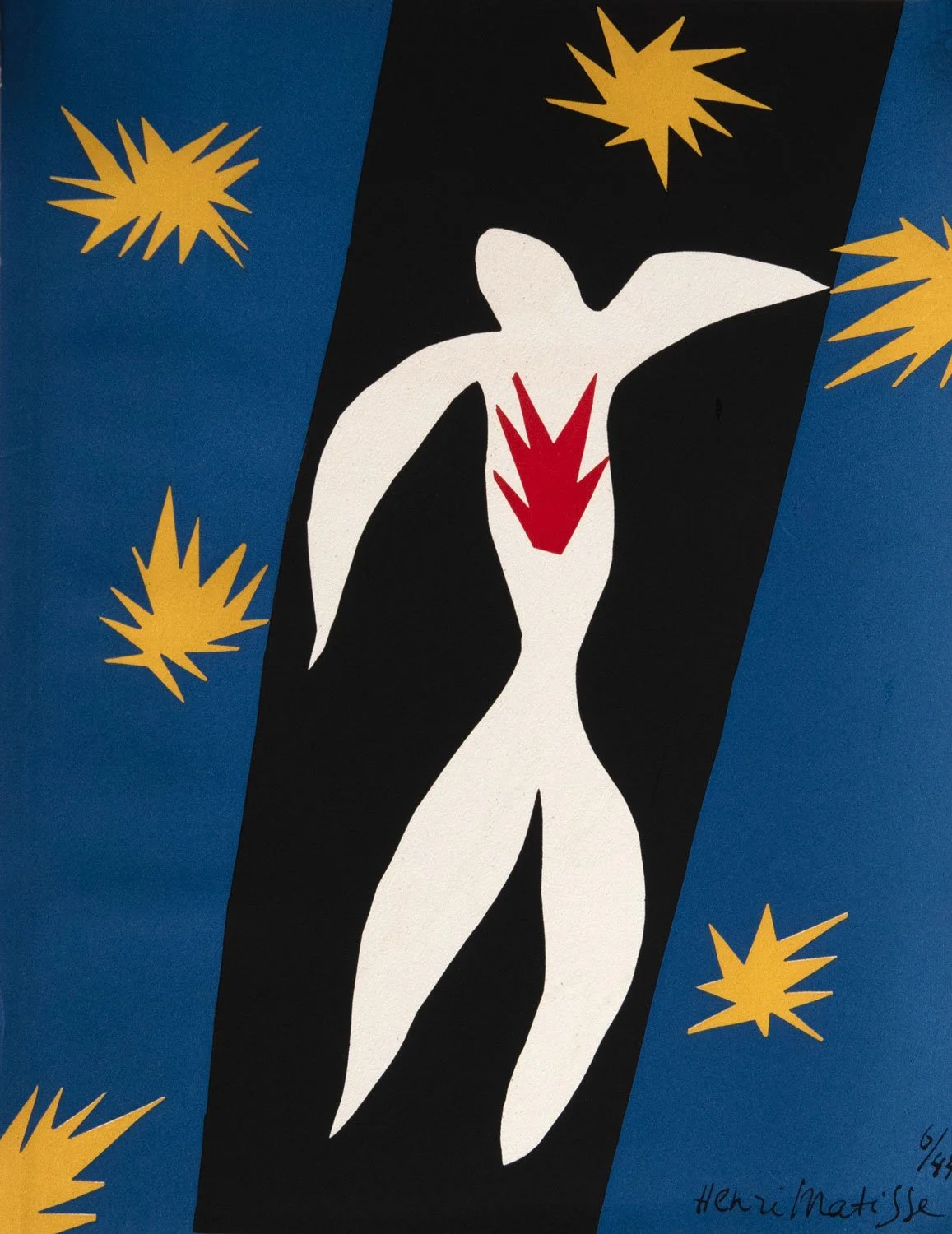

All of these painters were, in a sense, outsiders. And many of the great London paintings were executed by those originally from elsewhere. L.S. Lowry, a lifelong resident of English’s industrial northwest, embodied the city's bustle in Piccadilly Circus, London (1960), with crowds rushing beneath the stifling buildings and billboards of the West End. It was sold for £5.6m at Christie’s in 2012, a record for the artist.

BILL BRANDT, A Night in London, 1938, First Edition available at Hyraxia Books £3,250

The American master James Abbott McNeill Whistler spent the majority of his adult career in the city. In his twilit Nocturne paintings, he turned the Thames into a strange, dreamlike place. This not did always find favour with the natives — critic John Ruskin accused Whistler of “flinging a pot of paint in the public's face” after he exhibited the masterful, near abstract Nocturne in Black and Gold (c. 1875), an imagined depiction of a Chelsea pleasure garden. Whistler successfully sued for libel, but became bankrupt in the process. A few years earlier, his Thames Set (1871) of etchings had captured a rather grittier aspect of the city.These 16 prints deftly capture life on the city’s then thriving ports. "I assure you,” Whistler wrote to a friend, “that I have never attempted such a difficult subject”.

Another fascinating outsider-insider is the photographer Bill Brandt, currently the subject of a retrospective at Tate Britain. Brandt was born in Hamburg to a German mother and a British father who had spent most of his life in Germany, and spent his childhood in a Swiss sanitarium and under psychoanalysis in Vienna. But he disavowed his German origins and claimed himself a native of South London. In his 1930s photographs he captured the raw street life of the city as it had never been seen before, capturing everything from the aristocratic town houses of St. James to the tattoo parlours of Waterloo and the porters of Billingsgate fish market.

Bill Brandt, In the Public Bar at Charley Brown's, 1942 available at Holden Luntz Gallery $10,000

Brandt's 1938 photo book A Night in London (1938) did for the British capital what Brassaï’s Paris de Nuit (1936) had done for the French one, leaving no corner unturned. He later wrote: “I photographed pubs, common lodging houses at night, theatres, Turkish baths, prisons and people in their bedrooms. London has changed so much that some of these pictures now have a period charm almost of another century.”

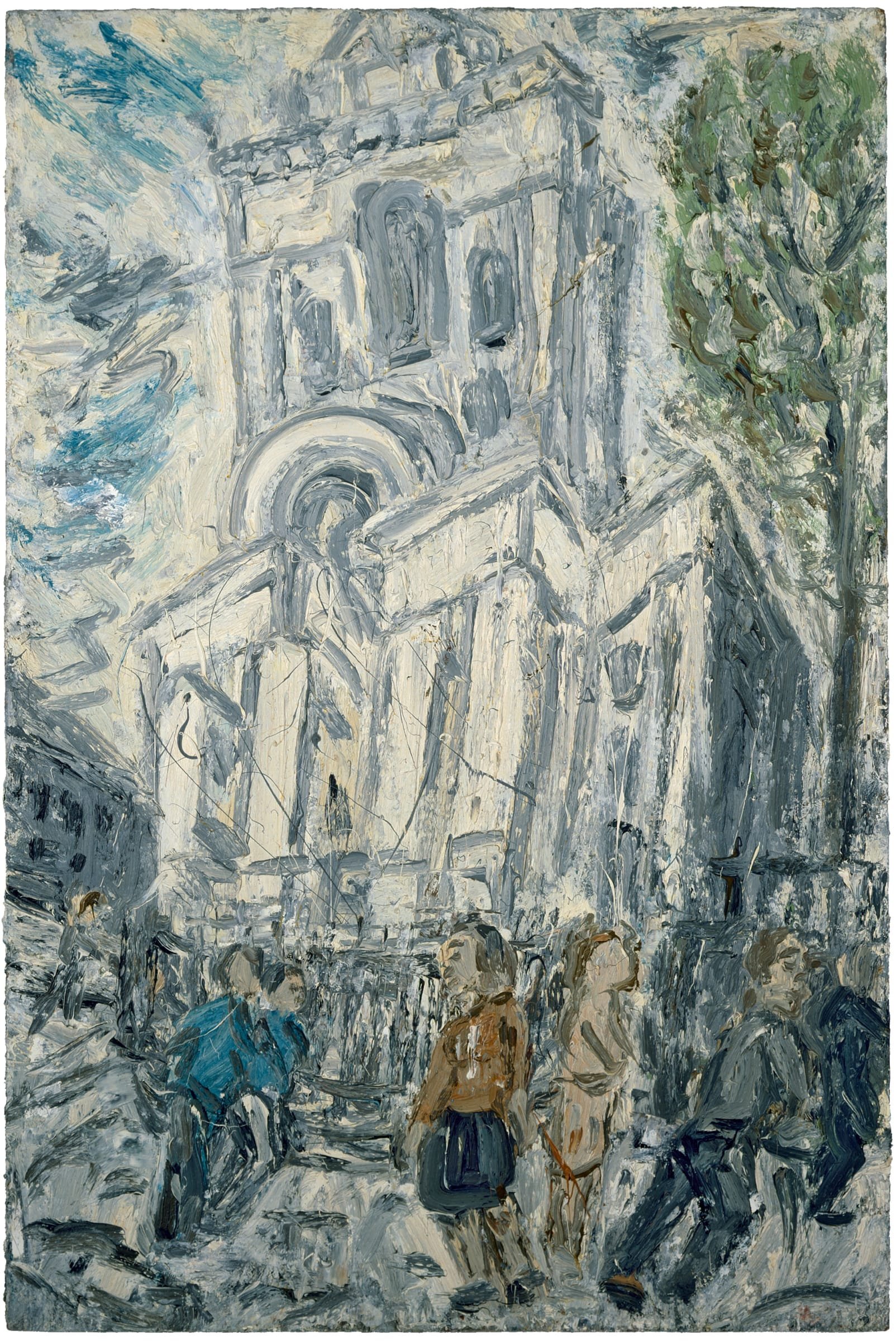

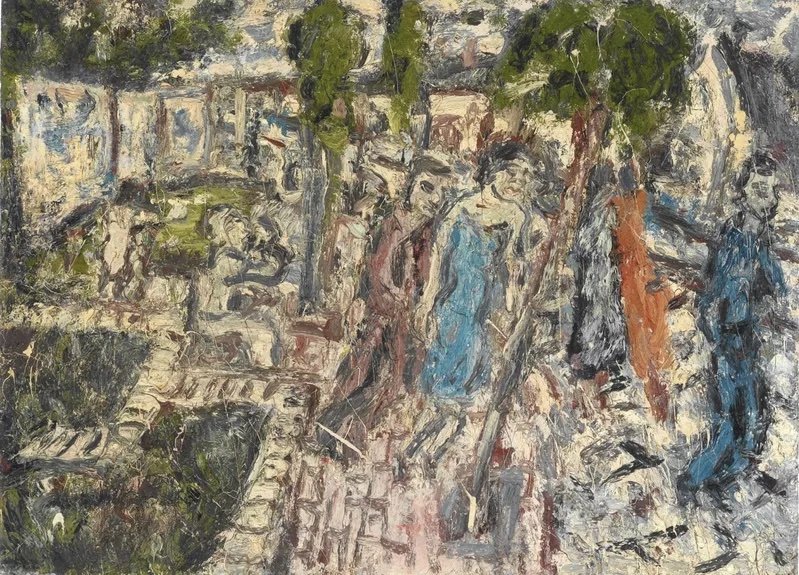

This constant change represents perhaps the greatest challenge for those artists aiming to capture the city. Yet there are two post-war painters who arguably do this better than anyone else. Frank Auerbach and the late Leon Kossoff capture their own patches of the city again and again, constantly resisting train tracks, building sites and junctions. Often rendered in heavy impasto, their London paintings show a dirty, fragmented, always moving city. Auerbach himself has repeatedly noted the difficulty of capturing the city: “I have a strong sense that London hasn’t been properly painted… But it has always cried out to be painted, and not been.” Auerbach acknowledged that many artists had captured bits and pieces, but no-one had truly grasped the whole.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Monet made several return trips to London where he took a room at the Savoy and painted the Thames. His extraordinary depictions of a fog-shrouded Westminster only convey a fragment of the physical city. But they also capture something bigger: a combination of the monumental and the fleeting that might reveal something of the ancient, ever-changing city as a whole.