The Souls of our Dead

29 April 2022

An extract from ‘The souls of our dead’, Patrick Galbraith’s chapter on seabirds, place, and art, taken from his new book, In Search of One Last Song, which is out now with William Collins, priced £18.99

Patrick Galbraith

Patrick is commissioning editor for The Open Art Fair magazine, as well as a journalist and author whose work has appeared in The Times, The Evening Standard, and The Spectator. He lives in South London with his terrier and is currently working on a play about lapwings, a bird that he has long felt deserves more time on the stage.

When John Cumming leans back, clasps his hands and raises them to his dry lips in thought, the little white dog he’s been stroking on his lap lifts its head, opens one eye, looks at me coldly for a moment, as though to say fuck you, then goes back to sleep.

It wasn’t until long after John’s uncle died that he finally sat down and typed up his fishing diaries. ‘That knowledge was intimate,’ he tells me, running the back of his hand over the dog’s soft belly as it rises and falls. ‘Every day he was noting down vivid descriptions of the sea’s colour. He wouldn’t have known it but he would have been observing the plankton, which colours and thickens the water, and that will affect where the fish are, but he was also noting the gannets and the fulmars and the kittiwakes.’ John suspects his uncle never knew the link between the sand eels and the plankton, but he remembers him talking about the connection between sand eels and fish. Lifting the coffee pot with unsteady hands, he pauses for a moment to pour himself another cup, then sits back in his chair and says that’s how it was for men of his uncle’s generation. ‘They would only find fish by observation of nature and the sea.’

‘Kittiwakes’ by Robert Vaughan

In the 1950s, when John was a boy on Burra, one of the smaller Shetland Islands – ‘never more than half a mile across, sheltered on one side and with the Atlantic on the other’ – he often went fishing in his uncle’s boat, but when he left school he decided it wasn’t for him and nor did he want to take on the family croft. Instead, he did what felt right and went to Aberdeen to study ceramics. Ever since, he’s been drifting back and forth, between Shetland and Orkney, drawing, and sculpting, and writing in response to all the things that have inspired him and the traces they’re leaving behind.

On John’s left, five scorched seabirds, blackened in his kiln, as though they’re the only survivors of a flock lost in an ocean fire, are spread out across a table. ‘I made a raft of these as an installation in a show,’ he says, passing me one. ‘I wanted to capture the fragility and that seabird presence.’ John’s wife, Fiona, who has been sitting by the large studio window, picks another off the table. ‘A disappearing race,’ she says to me, with a grim smile as she runs her fingers over the rough clay. The bird in my hand is twisted and brittle, with a large hole in its breast and its back covered in charred fragments. ‘I wanted to create something catastrophic,’ John tells me, looking down at the rest of the raft on the table. ‘There were 15 or 20 and I placed them all around the room.’ When John leans over to take the bird back, the small dog jumps off his lap and heads for the stairs.

In some ways, as a crofter who worked the land, John feels that his father’s relationship with birds was different to his uncle’s. He didn’t depend on them in quite the same way, but he’d grown up beneath a sky full of birdsong and he’d seen changes that saddened him. ‘On the small island where we lived,’ John tells me, ‘there were geos where the kittiwakes would settle and the rocks echoed with their voices.’ Outside, a pale wisp of cloud lifts and a beam of sunlight shines into the room, falling on John’s desk. Behind it, sixteen skulls, spread out along a shelf, are lit up white: a curlew, oystercatchers and kittiwakes. Following my gaze, John looks across at them for a moment, then turns back and continues, ‘When those kittiwakes returned, and their music began, that marked a time of year.’

On a chest in front of me, next to a small ditty box, five black books with an old map of Orkney on the front are stacked up on top of each other. A girl in the Stromness bookshop sold me the last copy in stock. ‘I know the guy who made that book,’ she told me. ‘He was the best art teacher I ever had, but there was some sort of disagreement and he left.’ She wasn’t clear, but it was something about wanting the students to actually make art rather than learning about the theory. As I lingered in the shop doorway, waiting for the rain to pass, she told me – leaning across the counter, with her cheeks in her hands – that she’s working on a novel of her own. There’s enough people she reckons who come to Orkney, stay for a while and write about it, but what about those who are actually from the island, what about their voices?

‘Was she a blonde girl?’ Fiona asks. ‘No,’ John replies, shaking his head, ‘that’s a lovely thing to hear. That would have been Freja.’ He leans forward to take the top book from the pile. ‘The whole idea of Working the Map,’ he says, passing it to me, was really about getting recognition for people who were aware years ago of changes. Before science was giving facts, your crofters and fishermen knew these things, but it didn’t really count because it wasn’t statistics.’ John looks over as I leaf through, returning to a page I’d read the previous evening, where a local accordion player talks about being ‘browt up ta believe that if you looked after the land, the land would look after you . . . you didna abuse the land, you cared for it.’ I ask John if he thinks that for all the land needed love, there was a feeling that the sea could look after itself. He leans back in his chair and looks around the room. Outside, over the meadow that runs down to the beach, six or seven swallows wheel across the marigolds then turn and fly towards the window before casting up over the house.

‘The sea when I was young,’ John tells me, lifting his eyes slowly, ‘was this vast thing. You know, it was just endless and cleansing. We thought it could cope with everything. We thought it was so big, and now in late life I’m thinking, my God, what have we done and will we get it back?’ There is a moment of silence and I’m not sure what to say but he answers before I do. ‘We can’t. We can’t get it back.’ As well as remembering the ocean as ever-forgiving, John also feared it in a way that he thinks people no longer do. ‘When I went to sea with my uncle there was one cabin. You lay there together and you could hear the water go past.’ As he speaks, he lifts his hand, and brings it slowly over the top of his head with his fingers outstretched. ‘There was a closeness then and a real vulnerability. With today’s super-trawlers and with all the technology, that’s been lost.’

Under the telephone wires, down in the field, a rabbit hops beneath a fence and disappears into the long grass. After John’s son finished school, he spent a while off the west coast in a Shetland trawler. ‘He’d be fishing round Rockall,’ John tells me, ‘and he’d say to the crewmen, what’s that bird there, and they would say, oh that’s a maa.’ Fiona stops him a second and tells me a maa is a gull. ‘Aye, a gull,’ he nods. ‘So then he’d ask, well, what’s that bird there and what’s that one there, and they’d say, oh that’s a maa.’ He clears his throat and shakes his head. ‘You see, I think, there’s a huge cultural shift between the fishermen of my uncle’s generation and the fishermen forever before that and the boys fishing today.’

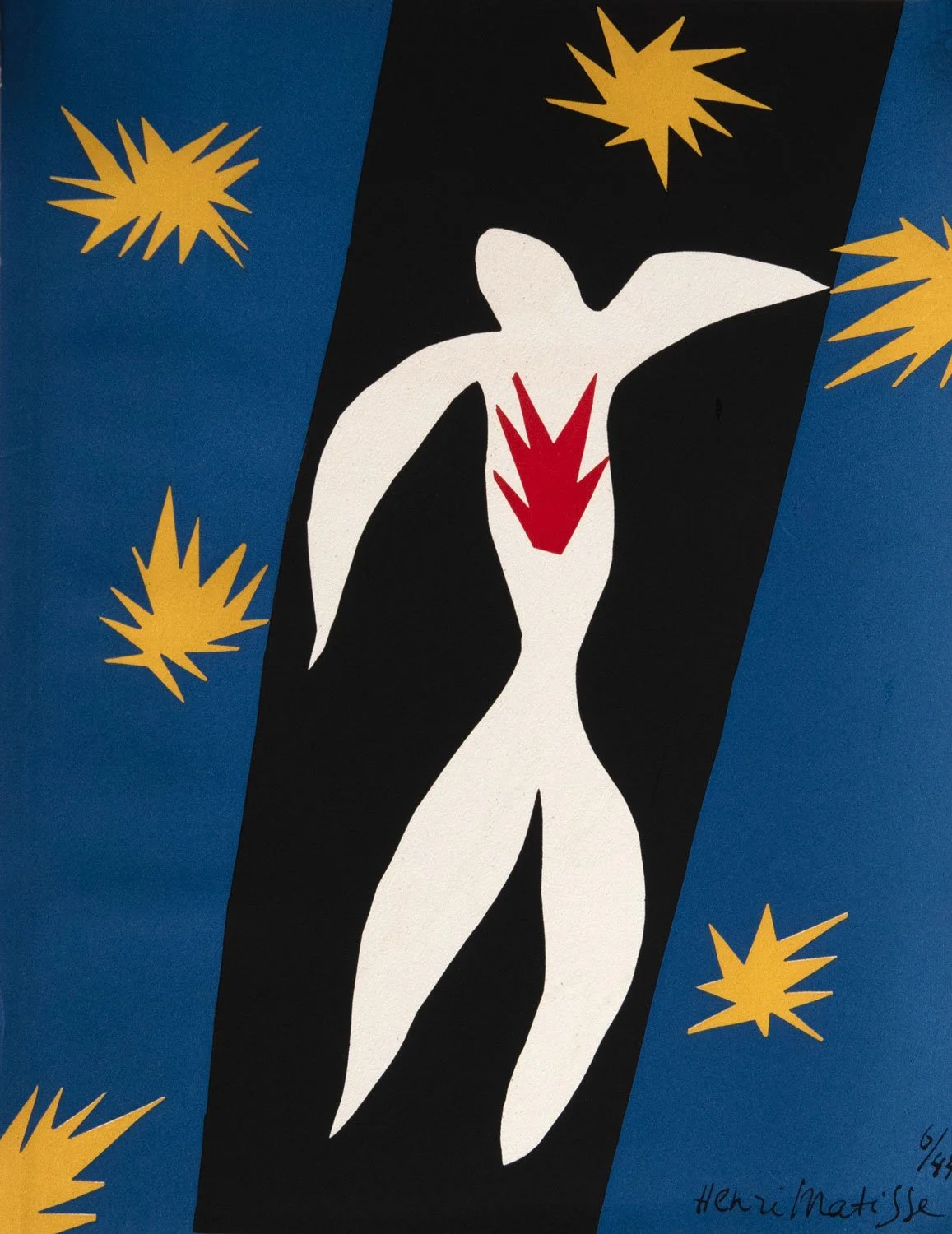

Cover art by Robert Gillmor

In the 1970s and ’80s, John remembers boats fishing for sand eel out of Shetland but he believes that’s largely stopped now. ‘They wanted them then for animal feed,’ he tells me, ‘but apparently now they’re fishing them to run power stations.’ Fiona laughs and says, ‘It’s the Danes apparently, but it’s quite unreal, isn’t it?’ John tells me somebody was recently talking to him about it and he found it hard to believe so he rang up his son, who eventually became a marine biologist. ‘The boy had a look and he said that’s absolutely right, Dad, and at that time there seemed to be 60 ships in UK waters fishing sand eel.’ Fiona stands up, puts the coffee cups on the tray and heads down out of the studio to the kitchen.

John thinks that when it all started to make sense to him was when he was on a boat, anchored overnight in the Minch with a number of other artists. ‘I was looking at the kittiwakes on the Shiants, there on the cliffs, and they were faring much better than the ones in the North Isles. I discovered later that there’s a big breeding area for sand eels just beyond there and I started to realise then what was really happening to these surface feeders.’ John remembers spending most of that trip sitting up on deck with a sketchbook, trying to capture the birds in flight. ‘I’m not there on deck doing those pastels,’ he says, pointing to two large drawings of kittiwakes hanging in the wind beneath an orange sky, ‘but I’m studying movement.’ He tells me he’ll show me and then stands and lumbers stiffly across the room to the bookcase beyond his desk. ‘Most of my work,’ he says as he looks along the shelves, ‘is couched in observation. It gives me a sense of when something’s wrong. You’ll be making a line and you get a real feeling that it’s not right.’ From among a row of hardbacks he pulls out two small pads and treads heavily, in his trainers, back across the carpet. ‘These wee kittiwake books,’ he says, passing them to me. ‘I did some sketches when I was on my last trip on an old herring boat sailing from Orkney to Shetland and then made these using silverpoint when I got back.’ John sits heavily. On every page he has sketched kittiwakes against the wind. Sometimes they are shadowy outlines, threes or fours, and sometimes there is a bird alone in great detail, dark wingtips and a darker eye.

The sun outside over the meadow has moved round and is casting John in a puddle of light. His hair is white and wispy and he has a shaving cut on his top lip, but his bright blue eyes aren’t those of an old man at all. ‘Lots of the people I recorded for Working the Map sat where you’re sitting,’ he tells me, smiling. ‘I think in the past, science and the observations of the islanders just didn’t meet. They haven’t respected each other. I wanted that book to do that.’ John remembers that when his father was alive he would often go and tell the scientists who would come to visit the island about the things he’d seen. ‘They would patronise him. He was treated as well-meaning but not informed. Their attitude really towards the crofters was that they knew about these things and they were going to tell us.’

Fiona appears back at the top of the stairs and perches on a wooden chair by the desk. ‘Would you mind just getting that urn?’ John says, pointing past her. She stands and lifts a dark clay pot from a shelf behind the skulls. ‘I spent a month walking Scapa beach to collect bird wrecks,’ he tells me as she passes it to him. With shaking hands John lifts it up and peers inside. ‘Have a look,’ he says, holding it out for me. ‘That’s a kittiwake in there.’ I tilt it into the sun and the light shines on the cremated remains of a seabird. Pushing my hand into the urn, I pick out a small piece of bone and rub it back and forth. In my sooty fingers, it crumbles into fragments and I let them fall among the ashes.

This is an excerpt from In Search of One Last Song by Patrick Galbraith, commissioning editor of The Open Art Fair magazine, out now in hardback with William Collins.