The World’s Biggest Wildlife Crime

2 June 2022

Ivory legislation is just the start: the protections for endangered wood have been changing.

Richard Negus

Richard Negus is a hedgelayer, wildfowler and conservationist who writes regularly for Shooting Times.

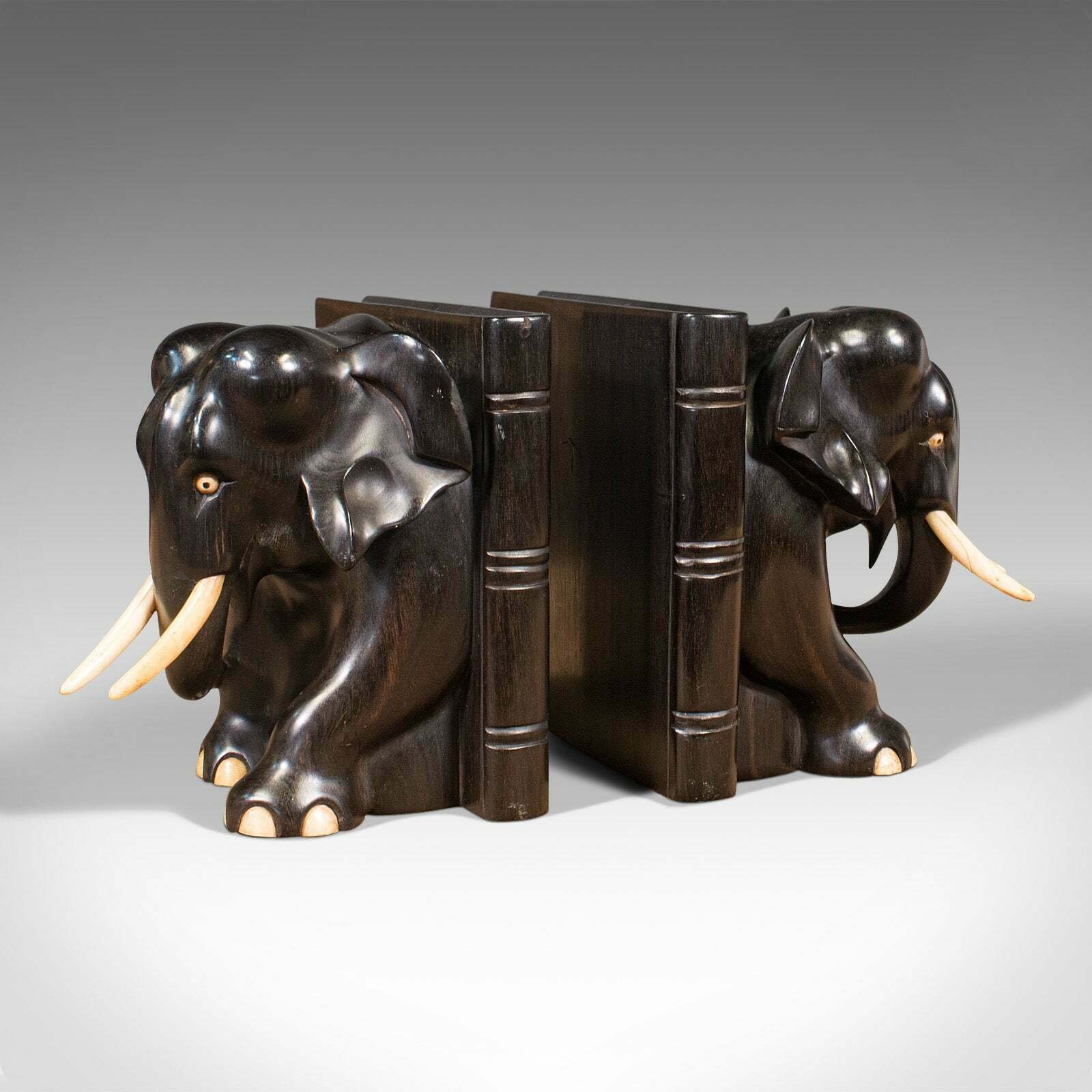

Pair of carved ebony elephant bookends, circa 1890.

Available from London Fine Antiques

My clearest memories of visiting my grandparent’s cottage is not of them, but of their things. A stentorian skeleton clock in the hall, a Victorian tin containing humbugs and a large and well foxed hand coloured photograph of a moustachioed relative in uniform, later killed at Spion Kop. At either end of their mantelpiece highly polished Ebony elephants teetered. Their mournful eyes and tusks were carved from ivory; my grandfather would use these yellowed pegs to tamp down the loose strands of Golden Virginia in his roll ups. It is amusing how those elephants, brought back from Africa by that great uncle (presumably before he was killed by Kruger’s commandos), could now be considered as dodgy contraband should I wish to sell them. It's not those tobacco stained tusks that are the problem, it is still legal to trade items containing less than 10% ivory volume made before 1947. That furbished Ebony is where a legal minefield lies.

The global concern over sustainably harvesting trees for their timber, and the biodiversity loss resulting from their felling, is growing. This concern has led to a number of species receiving felling controls or outright bans. Restrictions are overseen by two international bodies - the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) who focus on the legal side of things and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) who cover environmental aspects. CITES recognises, as with all fauna, three levels of threat to trees, the highest being those considered most imminently threatened with extinction globally – Brazilian Rosewood is one example. Red Stinkwood meanwhile is a Mid Tier, being at risk internationally in the wild but possibly prevalent in domestic locations. The lowest concern applies to trees under threat in specific geographic areas - as with Black Pine in Nepal. These protections don’t merely protect the tree whilst it stands, some also prohibit the production and retail of worked items – prayer beads made from Agarwood, Mexican Mahogany furniture or turned bowls from Monkey Puzzle. The dates when CITES recognised the threat to these tree species is important. Even if, as in the case of those mantelpiece elephants, the item is believed to have been crafted prior to its CITES listing – Madagascan ebony became Tier II in 2011 – the onus when selling, is on the retailer to prove it.

The IUCN endangered classifications, commonly known as the ‘Red list’, like CITES, fall under three categories – ‘Critically Endangered’ - species facing an immediate high risk of extinction, ‘Endangered’ -Not critically endangered, but still facing a near future high risk of extinction and ‘Vulnerable’. - a medium term high risk of extinction. Of course terms such as “immediate” and “near future” have a markedly different meaning for trees over other flora on the IUCN red list - three generations for trees can cover as many centuries. The Madagascan Ebony, from which I believe those elephants are crafted, is listed by the IUCN as a ‘Critically endangered’ species, which along with their Tier II label from CITES, makes them rare beasts indeed. Over 100 species of ebony are known to grow in Madagascar, some of which have completely disappeared in the wild due to unsustainable logging. Despite, localised or worldwide bans and restrictions issued by CITES and IUCN, many critically endangered trees continue to be felled, milled and smuggled abroad, either for specific use in musical instrument and furniture making or mixed up with general fellings to make veneers, chipboard and mdf. This illegal industry is estimated to be worth $150 billion, making it the world’s biggest wildlife crime. The question is therefore what can be done to protect what remains of these preciously rare trees?

An important pair of ebony, ivory inlaid and marquetry cabinets in the Louis XIII manner, attributable to Charles Hunsinger (1823 - 1893).

Available from Butchoff London

Dr Victor Leklerck is the Research Team Leader for World Forest ID, based at Kew. He and his team are creating the world’s largest collection of geo-referenced, open source timber samples. They are developing a database of chemical, isotopic, and anatomical reference material of these samples which can in turn be used to analyse timber and manufactured items as they enter customs borders. Supply chains are long, tracing illegally sourced timber back to its source had been nigh impossible. The work going on at Kew will enable identification of which tree species a piece of timber originated from and where and when it grew. Investigators will soon be able to uncover criminality the moment a timber product arrives at a port of entry. This is a crime that covers all continents. Frequently the end users, be they buying a sideboard from Ecuador, a guitar from Jilin or a mournful looking ebony elephant from Suffolk, is unwittingly abetting crime. This provenance verification, enabled by the work of Victor and World Forest ID, soon looks set to make the trade in illegal timber as hard as ebony for criminals to exploit.

Read more on the Kew Gardens website about Victor’s work.