Star Power

7 January 2020

Why a celebrity connection boosts the price - from a football legend’s tea set to presidential pottery.

Daisy Dunn

Daisy Dunn is a classicist and the author of, most recently, Homer: A Ladybird Expert Book, and an anthology entitled Of Gods and Men: 100 Stories from Ancient Greece and Rome.

Last month, a small lock of hair cut from Elvis Presley’s head in the 1950s sold at auction for £4,000. It came stuck to a piece of card bearing the name of the star’s hairdresser, Homer Gilleland of Memphis, who is known to have tended his – and his mother’s – tresses on several occasions. Sceptics might still question its authenticity (was this really one of the many locks Gilleland saved and pasted?) but clearly its provenance impressed in the sale room. Without that piece of card, after all, it would just have been a clump of coarse fibres.

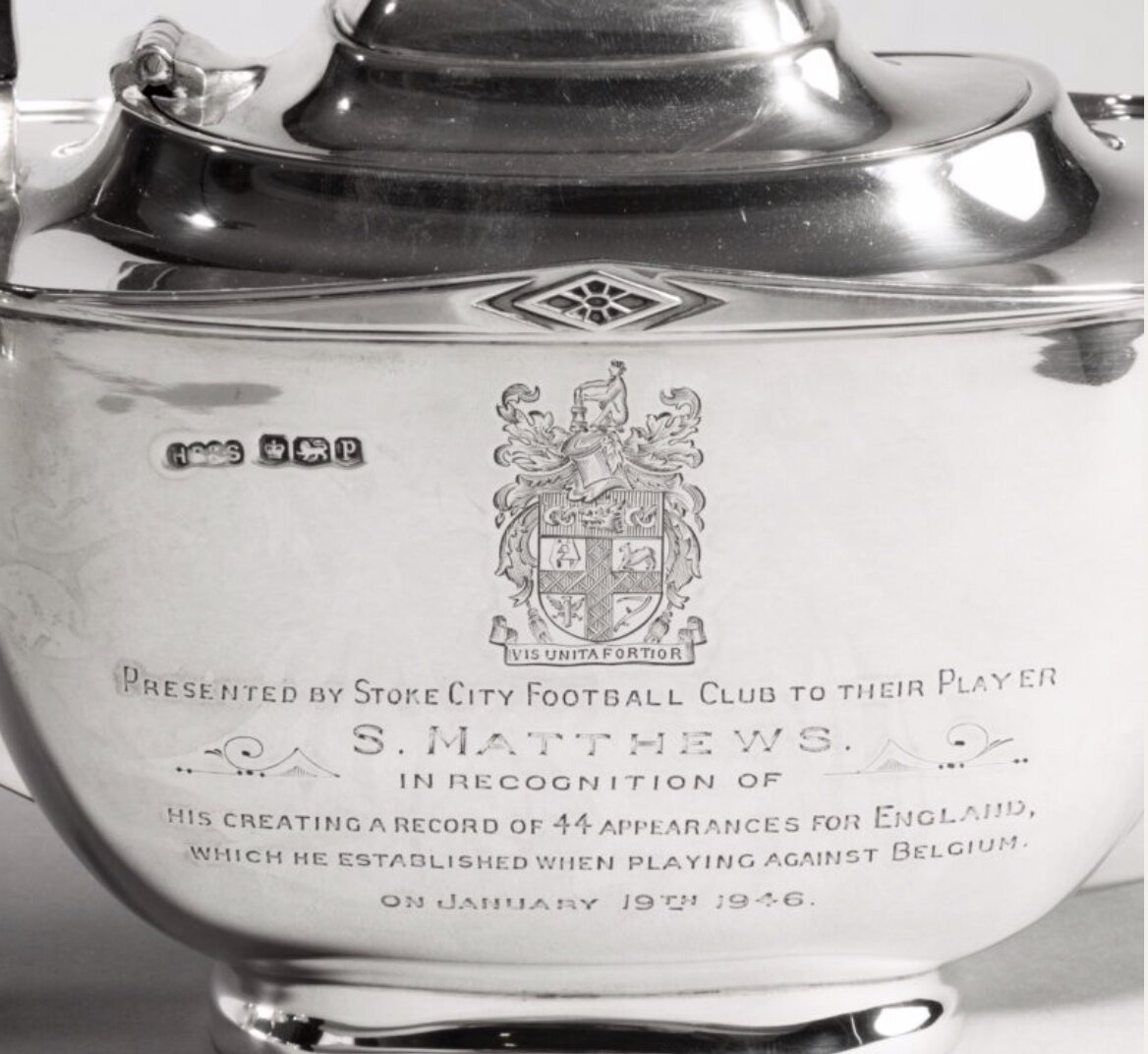

The same rule holds true of antiques. Objects with a credible celebrity provenance are often worth considerably more than their material value. A case in point is a four-piece Sheffield silver tea set from the 1930s currently on sale with Wick Antiques. It is certainly elegant, with its ovoid Art Deco shapes and high handles, but would hardly have warranted a price tag of £18,500 had it not been for its previous owner. The set was presented to Sir Stanley Matthews by Stoke City Football Club in 1946. The teapot is engraved with a dedication to the same effect, and the other pieces are monogrammed with the player’s initials, S M.

‘In the open market it’s just a nice quality tea set’, says Charles Wallrock of Wick. ‘If it hadn’t had a great provenance like this, I would never have bought it. I like buying things of a historical nature. I’d value it at £1,500-2000, maybe a bit more, if it didn’t have this Stoke provenance. Had it belonged to Lord Nelson or Emma Hamilton you’d be looking at something with a 1 in front of it – £100,000 and something’.

Wallrock in fact sold Lord Nelson’s seagoing silver just last year. Currently on his books are a translation of the works of Horace from Nelson’s library, worth £30,000, and the presentation silver salver to the Master Shipwright of Captain Cook’s Endeavour, priced at £12,500.

Buyers might justify splashing out on such objects by reflecting that they once formed part of an extraordinary life. Whether they accompanied their former owner across the seas, or sat by their bedside, they were within their sight, and their grasp, and might feasibly have helped shape their mood and thinking. You can even learn more about a person from their possessions than you can from an idealised gallery portrait.

Sales catalogues tend to emphasise connections between the pieces they are selling and illustrious former owners. When a blue and white Yongzheng vase once owned by Lou Henry Hoover was presented for sale in San Francisco earlier this decade, the director of the collection at Bonhams explained that the First Lady, a collector of Chinese porcelain, had been a great humanitarian.

A George II Silver Harvest Basket, London, 1759, by William Tuite. This basket was in the collection of Ernest, Duke of Cumberland the fifth son of George III, who became the King of Hanover in 1838.

Relatively recent celebrity ownership can indeed be just as important as historic ownership, especially where older objects are concerned. As Madeleine Perridge, Director of Kallos Gallery, which specialises in ancient pieces says, ‘It’s pretty rare to offer something owned by an emperor or with its ancient owner known, as the majority of such works are in museums – for example sculpture from Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. Of course, cameos from Imperial workshops do pop up occasionally, but there’s no way of knowing if Augustus used to sport one on his favourite toga! The quality and its more recent provenance are often as much a key factor in value’.

Perridge advises that classical pieces passed down through a single family since the time of their acquisition, perhaps in the 18th century, are of particular interest to buyers. Such pieces with celebrity names attached are all the more covetable.

To own something that once adorned the home of someone celebrated naturally grants certain bragging rights among friends and guests. As Charles Wallrock observes, ‘To be able to say, “This came from Chatsworth”– it’s everything’.